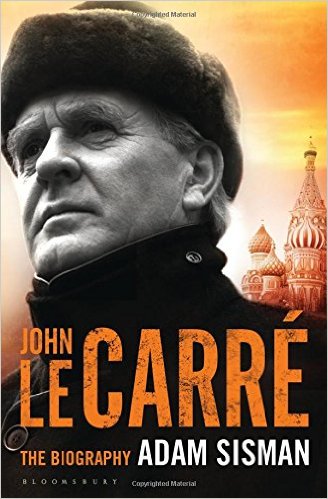

(Bloomsbury: London, 2015). 652 pp. incl. index. ISBN: HB: 978-1-4088-2792-5 TPB: 978-1-4088-2793-2 ePub: 978-1-4088-4944-6[ buy this book ]

I thought to review this book because I had enjoyed the spy novels of John le Carré and, having introduced a chapter on secret intelligence into the latest edition of my textbook and mentioned him in it (p. 155), was keen to see if Adam Sisman had turned up anything new about the novelist’s own short career as an intelligence officer in what was then West Germany. In the event, this was the only disappointment of The Biography because it was the one subject on which le Carré – whose real name is David Cornwell – refused to speak to the author. (It looks as if we shall have to wait a long time for this particular story, which will no doubt be mentioned in the still secret post-1945 official history of the Secret Intelligence Service said to have been written by Gordon Philo, aka ‘Charles Forsyte’ – see in the section headed ‘Novels by former Diplomats and Intelligence Officers’ on this page.) Having said that, what Sisman does tell us is that, having initially been thought disloyal by SIS for depicting his former colleagues as ‘unscrupulous or, worse, incompetent’ in the novel that made his name – The Spy who Came in from the Cold (1963) – by the 1990s, if not before, le Carré was once more persona grata at SIS headquarters in London. This was chiefly because of his portrayal of George Smiley, the central figure and successful mole-hunter in later novels. ‘Taken as a whole,’ writes Sisman, ‘David’s oeuvre had portrayed British intelligence as highly effective in the Cold War – arguably, as much more effective than it had been in reality.’ In short, SIS had come to like le Carré because he improved their reputation, both at home and abroad (pp.520-1).

Despite telling us nothing new about the subject’s own career as an intelligence officer, in every other regard this lucid, exhaustively researched, and admirably even-handed biography will be read with great enjoyment by all le Carré fans. There is much fascinating – even shocking – detail on the subject’s early life, particularly his relationship with his father Ronnie, an adept and outrageous swindler who even sought to blackmail his own son. The treatment of le Carré’s dealings with his various publishers as his novels began regularly to hit the number one spot on the US bestseller list is also instructive. For those who have occasionally struggled with the plot-line of some of the spy novels, have difficulty in placing the characters in his cast lists, or would be interested to know which features of persons in le Carré’s own life shaped these fictional individuals, Sisman’s detailed accounts of each novel and how they were written will prove absorbing. It is also most interesting – and a mark of the biographer’s detachment – to give space to criticism as well as praise for the novels, especially the later, polemical ones; for example, Hilary Mantel’s savaging of The Constant Gardener in the New York Review of Books. Other critics given a respectful hearing include John Updike and the always incisive and entertaining British-based Australian, Clive James.

I was also impressed by the attention that Sisman gives to le Carré’s method of writing and research. It might well be presumptuous of me to say so, but I think that any teacher of what it is now fashionable in higher education to call ‘creative writing’ could do far worse than put this book high on their reading list. It is unfortunate, therefore, that the lengthy Index – almost entirely just a proper name index – was not drawn up with The Biography’s value in this regard also in mind. There is no guide in it to pages (350-3, for example) dealing with ‘plot development’, ‘character collection’, and so on. I think that Sisman has missed a trick here.

As I have already indicated, although it bears repeating, Sisman’s book is by no stretch of the imagination a hagiography. Le Carré, he at least strongly hints, sometimes cannot tell the facts of his life from his own fiction, and occasionally writes so obscurely that even someone as close to his mind as his own biographer cannot understand him. Neither does he shrink from describing what seems to be the rather ruthless treatment meted out by his subject to publishers and agents who had served him loyally for many years but eventually been found wanting in energy or imagination; nor from recording le Carré’s inability, now and then, to resist the temptation to engage in venomous public exchanges with fellow writers such as Salman Rushdie – one of the last chapters is headed ‘Mr Angry’. In any case, who is perfect? These failings – if such they are – pale in comparison with Le Carré’s skills and industry as a novelist, his later acts of charity, and his willingness to court critical attack by using his more recent books as vehicles for attacking the corporatism of our age, not least – in this case with some success (p. 536) – in the shape of the not altogether benign influence of the global pharmaceutical industry. To these outstanding merits The Biography does full justice; it is a work worthy of its subject.