27 January 2024

For a long time, China had felt the need for more space for its embassy in London than that provided by its existing diplomatic premises in Portland Place, near Regent’s Park. As a result, having been given the go-ahead by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (a requirement under Section 1 of the Diplomatic and Consular Premises Act 1987), in May 2018 China paid £255m for the Royal Mint Court site on which to erect its new diplomatic mission. Plans were subsequently drawn up by award-winning British architect David Chipperfield and placed before the Tower Hamlets’ planning department in June 2021. At 65,000-square metres, it would be China’s biggest embassy in Europe, almost double the size of its mission in Washington and even bigger than the new US embassy in London.

Many objections to the project were registered, among them worries over threats to heritage assets and local fears that the embassy would lead to increased traffic congestion, produce a risk to neighbourhood security from possible terrorist attacks and become a secret police station. What was known by the planners as a ‘non-material’ objection became one of the opposition’s most telling weapons. This was the political hostility to the proposed development of local Muslims – who are numerous and influential in Tower Hamlets – because of China’s reputation for mistreating its Muslim Uyghur people. It was even threatened that, as a demonstration of local sentiment, streets in the vicinity would be re-named ‘Tiananmen Square’, ‘Uyghur Court’, ‘Hong Kong Road’ and ‘Tibet Hill’. To cap it all, the well-publicised violent behaviour of the Chinese consul towards a peaceful protester outside his premises in Manchester in October 2022 provided opponents of the new embassy plan with further telling ammunition: who would want a fortress of ‘wolf warrior’ diplomats for neighbours?

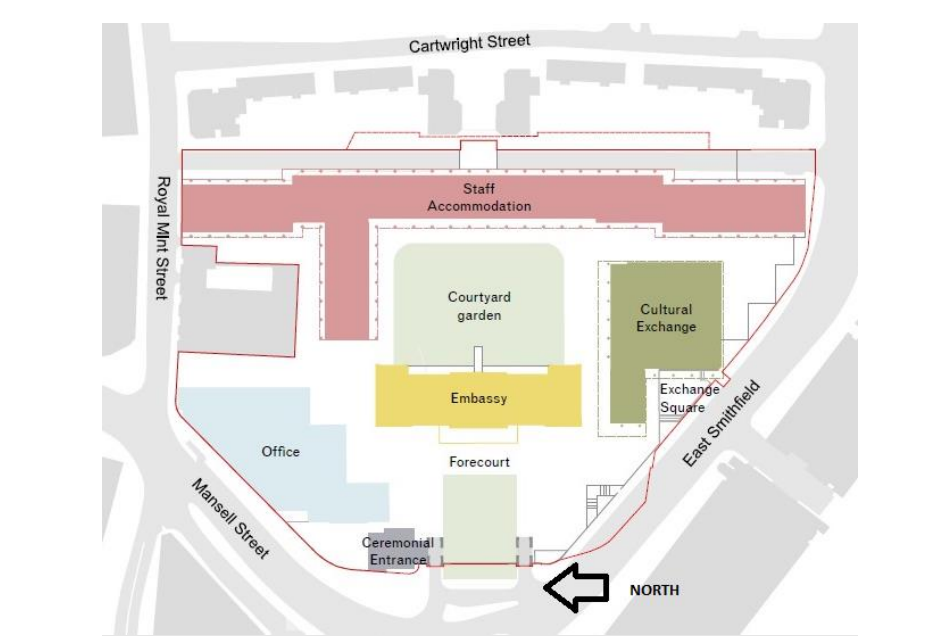

Proposed layout of new Chinese embassy in London (Tower Hamlets).

The Tower Hamlets’ planning officers certainly did their best for the project. In a lengthy report dated 1 December 2022, which was packed with attractive illustrations, they concluded that the proposal was well designed and ‘would deliver a high quality, well integrated, inclusive and sustainable place.’ Consequently, subject to China’s signature of a legal agreement to observe a long list of planning obligations and conditions, for example on archaeological, energy and sustainability matters, they recommended acceptance of the plan. Nevertheless, on 2 February 2023 the Tower Hamlets’ borough council unanimously refused permission, and London mayor Sadiq Khan declined to overrule its decision.

Recognising that a formal appeal would be useless, China urged the British government to weigh in on its behalf and overrule the local objectors, eventually going public with its frustration. Britain, its foreign ministry announced, had an ‘international obligation to facilitate and support the building of premises of diplomatic missions.’

Unfortunately for Beijing, the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations (1961), to which the Chinese Foreign Ministry statement was an obvious allusion, did not unambiguously support its pitch. It is true that it states that ‘The receiving State shall either facilitate the acquisition on its territory, in accordance with its laws, by the sending State of premises necessary for its mission or assist the latter in obtaining accommodation in some other way’ (Article 21.1). But, as Eileen Denza points out, the word ‘facilitate’ was never defined by the International Law Commission, and what this article actually signifies is that in this matter the receiving state’s duty is only one of conduct rather than one of result (Diplomatic Law, 4th ed. OUP, 2016, p. 106); that is, in plain language, the receiving state is not in breach of the Convention if, despite its best efforts, difficulties of one sort or another make it impossible to deliver exactly the result sought by the sending state.

No doubt standing on this interpretation of Article 21.1of the VCDR, the FCO probably told the Chinese government that there was nothing further it could do for its embassy project. It might also have been stiffened in this attitude by a cautionary observation in the report of the Tower Hamlets’ own planners; namely, that because of the UK’s State Immunity Act 1978, compliance with China’s obligations and conditions in implementation would probably be unenforceable other than by diplomatic pressure. And since already by 2019 the ‘golden era’ of Sino-British relations had come to an end over the Hong Kong democracy protests, this avenue was not likely to be promising. By the early autumn of 2023 the business and architectural press had written off China’s Royal Mint project, although as far as I can see no official statement on the subject has been made.

Proposed and existing layout of Chinese embassy in London (Tower Hamlets).

At least two points of general significance emerge from this story. First, as just noted, the impact of any state immunity legislation on the enforceability of conditions attached to planning consent for a new embassy has to be taken into account, although it is safe to assume that such legislation in most other states is less indulgent than that of the UK, thereby making legal enforcement easier. Second, finding a site for a large new embassy in an old city where local opinion cannot simply be brushed aside is extremely difficult, even when the sending state is powerful and can afford first class architects. This is why it is particularly in such circumstances that it is better for a sending state to negotiate a special international agreement ‘rather than rely on the somewhat weak provisions of Article 21 of the Vienna Convention’ (Denza, Diplomatic Law, p. 108). Had a special agreement on the Royal Mint project been concluded in 2018, it would presumably have been easier – although not necessarily in the interests of the borough of Tower Hamlets – to get the new embassy launched. But the Chinese probably thought that London needed its investment so badly, and would also require their own approval for Britain’s plans to rebuild its own embassy in Beijing, that the Conservative government would help it out, come what may. Add to this the fact that Boris Johnson was foreign secretary at the time and a complete mess was probably unavoidable.

Note on sources: The full report of the Tower Hamlets’ planning officers on the new embassy plan submitted by the ‘Chinese Embassy UK’, together with the Council’s report refusing permission, can be found via this page on the Tower Hamlets Borough Council website. Tick and download the first two, 10 and 9 February 2023.