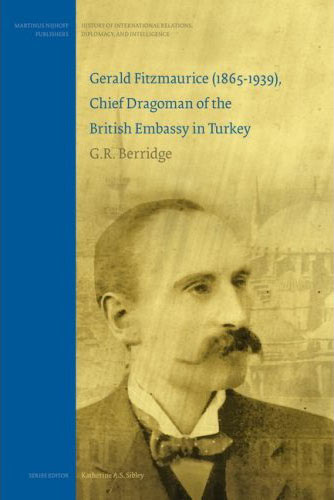

Gerald Fitzmaurice (1865-1939), Chief Dragoman of the British Embassy in Turkey

(Martinus Nijhoff: Leiden, 2007)

G. R. Berridge

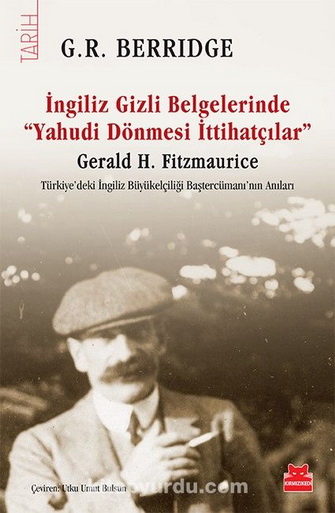

Published in Turkish translation under the title Gerald H. Fitzmaurice: İngiliz Gizli Belgelerinde ‘Yahudi Dönmesi İttihatçılar’ (Kirmizikedi, Istanbul, 2011), and pirated by the Internet Archive

The book has thirteen black and white illustrations and four maps. Like all my books, it has a full analytical index.

At the end of the 1990s I commenced an ambitious project to write a history of the British Embassy in Turkey. I did a great deal of work on this but other things came up, including the offer to be the Associate Editor on the Oxford [then New] Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB) with responsibility for 20th Century diplomatists. I accepted this, and among the essays I sought to commission was one on Gerald Henry Fitzmaurice, whom I had discovered to have the reputation for being the real power in the British Embassy in Constantinople before the First World War. Fitzmaurice had as yet no biographer, so there was no obvious candidate for authorship. Casting around also failed to turn up anyone willing and able to do it.

By this time Fitzmaurice had also started to interest me for another reason. He was a classic example of an important kind of diplomatist that I had come to think was too neglected by scholars; namely, what the ancien regime called a ‘minister of the second order’. In the late seventeenth century Abraham de Wicquefort had written a short chapter on such ministers in his landmark work L’Ambassadeur et Ses Fonctions and, having been one himself, remarked naturally enough that “princes would be more inconvenienced from the want of these ministers than from that of ambassadors”.

However, despite the prejudice, I found the argument convincing: not having the ‘full representative capacity’ relative to his sovereign that was the burden of his ambassador, a minister of the second order could take risks in pursuit of intelligence and influence that his chief could not. But diplomatic historians have been mesmerised by ambassadors, Wicquefort’s ‘comedians’. (Not surprisingly, there is no biography of Wicquefort himself.) Moreover, despite the libraries of books that have been written about the great Niccolò Machiavelli, another minister of the second order, relatively little has been written about his diplomatic career. Even his diplomatic despatches – despite the fact that they contain the earliest expression of some of his key ideas, as Quentin Skinner has pointed out –have only once been translated into English and that was in the late nineteenth century by a (very gifted) German-American railroad surveyor and engineer. With these thoughts in my mind, I concluded that a study of Gerald Fitzmaurice might also throw light on a neglected question of more general significance in the history of diplomacy. In the end, therefore, I decided to write the article on him for the ODNB myself – and hence eventually the present full-length biography. I suppose I should be flattered that it has been pirated by the Internet Archive for free borrowing but that isn’t the only feeling this discovery has provoked.

However, despite the prejudice, I found the argument convincing: not having the ‘full representative capacity’ relative to his sovereign that was the burden of his ambassador, a minister of the second order could take risks in pursuit of intelligence and influence that his chief could not. But diplomatic historians have been mesmerised by ambassadors, Wicquefort’s ‘comedians’. (Not surprisingly, there is no biography of Wicquefort himself.) Moreover, despite the libraries of books that have been written about the great Niccolò Machiavelli, another minister of the second order, relatively little has been written about his diplomatic career. Even his diplomatic despatches – despite the fact that they contain the earliest expression of some of his key ideas, as Quentin Skinner has pointed out –have only once been translated into English and that was in the late nineteenth century by a (very gifted) German-American railroad surveyor and engineer. With these thoughts in my mind, I concluded that a study of Gerald Fitzmaurice might also throw light on a neglected question of more general significance in the history of diplomacy. In the end, therefore, I decided to write the article on him for the ODNB myself – and hence eventually the present full-length biography. I suppose I should be flattered that it has been pirated by the Internet Archive for free borrowing but that isn’t the only feeling this discovery has provoked.

Contents

- Nearly a priest, 1865-91

- Armenia and Constantinople, 1891-1902

- Between two fires: the Yemen frontier, 1902-5

- Chief Dragoman at last, 1906-7

- Revolution, 1908

- “Old regime though not reactionary”, 1909-11

- Troubleshooting in Tripoli, 1911-12

- Retreat from Constantinople, 1912-14

- Political warfare, 1914-21

Epilogue

Addenda

In late March 2017 I received an email from Caroline Mullan, the Archivist of Blackrock College in Dublin who gave me so much help with this book that it was to her that I dedicated it. Attached was a scan of a letter about Fitzmaurice which had just come into her possession. It is dated 1968 and was sent to Father John Ryan, who collected material on former college students. Written by another former student, Robert Cussen, this contains information based on the recollections of Denis Gwynn (1893-1973), the Irish journalist and academic who as a young man knew Fitzmaurice well. Some of the information is new (including the fact of the relationship with Gwynn) and some adds valuable support to existing knowledge: (1) Fitzmaurice’s parents lost all of their property in consequence of the failure of ‘the old Munster Bank’, which I did not know and therefore did not report in the book; (2) Fitzmaurice abandoned his plan to be a priest and instead joined the Levant Service because he contracted tuberculosis, which I did not know either, although the letter is vague on this point – perhaps it was felt that Fitzmaurice was more likely to recover his health as a consul in the Levant than as a missionary in Africa (compare pp. 5-7, ‘Change of direction’, in my book); (3) he had ‘a break down during the first world war’, which confirms what I had concluded; and (4) after the war, ‘he lived like a hermit in a London boarding house, always trying to raise money for chapels and churches dedicated to Saint Patrick’, which is consistent with the picture I drew from other sources (Epilogue, pp. 246-8). Gwynn was a prolific writer (see his list of publications in the Wikipedia article) and I imagine that a future scholar interested in Fitzmaurice would want to trawl his output for any references to the ‘Wizard of Constantinople’.

Another fact recently turned up by Caroline is that Alice, the sister to whom Fitzmaurice left the greater part of his estate (Epilogue, p. 248, fn. 22), was almost certainly a school teacher.

Reviews

David Barchard, Cornucopia

Saul Kelly, Diplomacy & Statecraft

Charles Malouf Samaha, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society

Roger Adelson, International Journal of Middle East Studies

… Berridge relies more on the sources than the opinions of Fitzmaurice or how he was viewed by his contemporaries in Constantinople and London, as well as by historians today. By avoiding sweeping judgments, Berridge can present the ups and downs as well as the personal pettiness and careerism surrounding this controversial figure.

… Berridge does not regard Fitzmaurice as mad or stupid, much less ill-informed about the Young Turks. This reviewer published Mark Sykes: Portrait of an Amateur (London: Jonathan Cape, 1975) about another secondary British figure about whom opinion still remains divided. Like Fitzmaurice, Sykes was a Roman Catholic who distrusted Masons and Jews before 1914 and backed Zionism during World War I. …The influence and views of Fitzmaurice and Sykes shifted with circumstances, as Berridge makes clear in his account of Fitzmaurice.

… Fitzmaurice worked very hard to fill various roles and had views of his own from the Young Turk Revolution in the summer of 1908 to the outbreak of war with the Turks in the fall of 1914. This book makes it clear that it is a gross simplification to label Fitzmaurice pro-Old Turk and anti-Young Turk.

Berridge contributes less to our understanding of Fitzmaurice and the role he played for the British during World War I. This may come from wartime London being such a vastly different context than the British embassy in Constantinople before 1914. This may arise from the secrecy surrounding Fitzmaurice’s work for naval intelligence and the political department of the Foreign Office, not to mention special assignments, where he was usually passed over by most of the individuals and agencies involved with British war policy. After the war, the impecunious, chain-smoking, and hook-nosed Fitzmaurice was dismissed as too eccentric by most people. He died in relative obscurity.