2 February 2024

On 8 December 2022, appearing by video link at the Old Bailey in London, Anne Sacoolas, US citizen and wife of an intelligence officer at an American diplomatic communications hub at Croughton in the English Midlands, was sentenced to eight months in prison, suspended for a year, for careless driving. On 27 August 2019, she killed the young British motorcyclist, Harry Dunn, while driving on the wrong side of the road. This was the high-water mark of a case that cast into sharp relief the provision on embassy annexes of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations 1961 (VCDR) and, in the process, caused a significant ripple in Anglo-American relations.

In 1963, the US airbase at RAF Croughton was authorised by the UK for use as a relay point for US government diplomatic communications, and by the early 1990s it was on the point of being run entirely by Department of State personnel instead of Department of Defense civilians. In early July 1994, therefore, the US Embassy in London began to press the Foreign and Commonwealth Office for recognition of the base as one of its own offices (High Court, paras. 21–36) pursuant to Article 12 of the VCDR. This allows sending states, provided they have the prior express permission of the receiving state, to ‘establish offices forming part of the mission in localities other than those in which the mission itself is established.’ The Embassy also asked for its buildings to be recognised as ‘diplomatic premises’ pursuant to the UK’s Diplomatic and Consular Premises Act 1987 and for its staff to be ‘included on the Diplomatic and Administrative and Technical [A&T] lists.’ Those on the diplomatic list would be senior managers described as ‘communications attachés’. Jonathan Sacoolas, Anne’s husband, was classed as A&T staff.

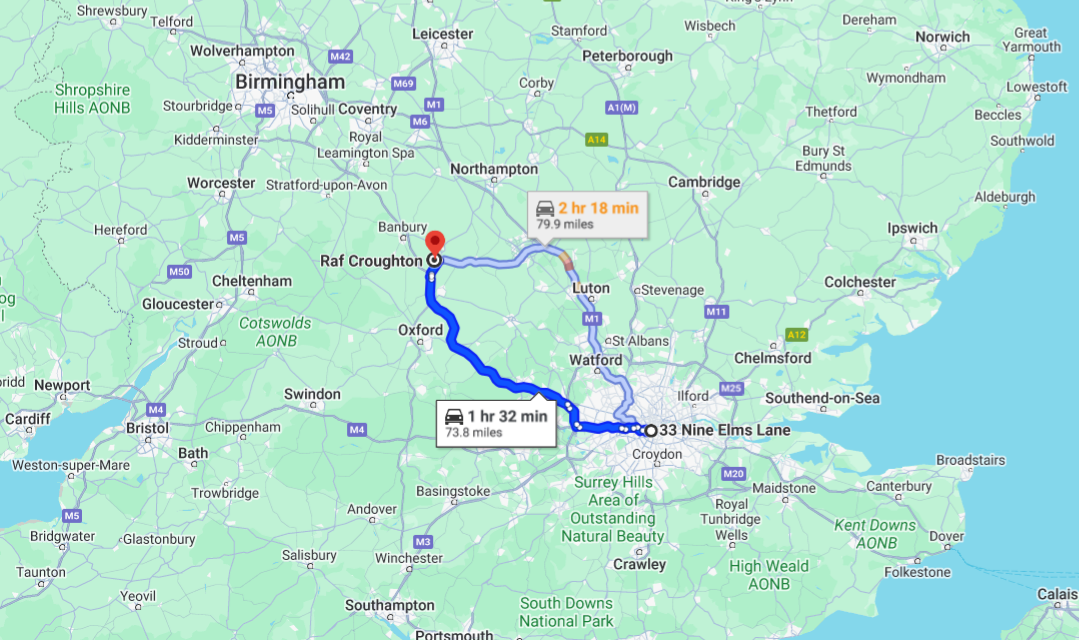

A route map from the US Embassy at 33 Nine Elms Lane in London to its ‘Annex’ in Croughton (Google Maps, February 2024).

In the discussion of ‘offices away from the seat of the mission’ by the International Law Commission (ILC) and subsequently on 15 March at the UN conference that launched the VCDR, Article 12 (7 and then 11 in earlier drafts) was generally agreed to be necessary chiefly because summer embassies were common in hot countries. It was also mentioned that naval and commercial attachés might wish to have an office in a port. But the latter – who were analogous to the American proposal for communications attachés at Croughton – were not at all common. As a result, the Protocol Directorate in the Foreign Office, on which responsibility for this matter fell, appears to have been rather startled by the US Embassy’s requests.

It became clear in evidence given at the High Court much later that the Protocol Directorate was particularly uneasy about the large number of A&T personnel who would acquire privileges and immunities under the US Embassy’s proposals for its ‘London Annex Croughton’; for, except that under the Vienna Convention, they have no immunity from civil and administrative jurisdiction while engaged in private matters, their privileges and immunities are otherwise identical to those of diplomatic officers. Moreover, the Croughton base was isolated, and its distance of about 70 miles via the M40 from the embassy in London, then in Grosvenor Square, was not short by British standards. These factors together led an official in Protocol to ruminate – prophetically as it turned out – that there was ‘perhaps a greater risk of such staff becoming involved in incidents (e.g. drunk driving, speeding, parking etc.) … than there would be in London and this [sic] focussing public attention on the facility and its special status’ (High Court, para. 27). It is probable that Foreign Office anxiety on this point was accentuated by the traditional view that A&T staff were ‘more likely to neglect their obligations or to commit offences in the receiving State since they are less restrained by the professional traditions and discipline of a diplomatic service’ (E. Denza, Diplomatic Law, 4th ed., 2016, p. 328).

In the event, therefore, the Foreign Office accepted the US Embassy’s requests on condition that it would agree in advance to waive the immunity of A&T staff at Croughton from criminal as well as civil jurisdiction over actions outside their official duties. This ‘advance waiver’, as it was known, was accepted by the Embassy and duly registered in the Exchange of Notes in which the negotiations culminated in 1995. (Further increases in staff numbers were agreed in the years 2000–2006.) Unfortunately, presumably because of sloppy drafting or because the US side thought wives might make a difficulty about being stuck in a Northamptonshire backwater without special preference on the point, the advance waiver omitted to include family members. And because the US Embassy insisted on this, and an urgent search of Foreign Office archives failed to produce any evidence to challenge its position, nineteen days after the incident the State Department whisked Anne Sacoolas back to the USA. A Foreign Office request for the waiver of her immunity had been refused, and later pressure for her extradition to face trial in England was denied amidst some acrimony. To the chagrin of Harry Dunn’s family and supporters, on 24 November 2020 the High Court – like the Foreign Office – was also obliged to confirm Mrs Sacoolas’ immunity from British criminal law.

Meanwhile, in view of the extensive coverage of the case in the British press, on 20 December 2019 the foreign secretary, Dominic Raab, who was reportedly ‘incandescent’ about the US attitude, had announced a review of ‘the immunity arrangements’ at the Croughton air base with a view to making sure that nothing like this could happen again. A new Exchange of Notes was duly agreed upon with the Americans and announced in bare outline by Raab on 20 July 2020. This not only ‘expressly’ extended the US advance waiver of immunity from criminal jurisdiction in respect of acts outside official duties to the family members of US staff at the annex but to all embassy staff serving there, not just A&T staff. Finally, it contained a new waiver in respect of at least one of the Vienna Convention’s provisions on inviolability (the full text has not been revealed) as distinct from immunity from jurisdiction – the right to complete protection from arrest and detention.

This was quite a turnaround, possibly achieved by Raab’s characteristic bullying of his civil servants in the Foreign Office (Tolley Report, paras. 151, 152, 156.3) – who were more likely than him to be indoctrinated in the VCDR – into submission. What is particularly striking about the new Exchange of Notes is the erosion not only of the immunities from jurisdiction and personal inviolability of A&T staff and their families but of those of the highest class of embassy staff and their own families; namely, diplomatic officers – the communications attachés. It was almost certainly this that was in the mind of the chairman of the House of Lords International Agreements Committee, Labour peer and former attorney general, Lord Goldsmith, when in a sharp, published letter to Dominic Raab, he challenged the Foreign Office’s refusal to let his committee see the full text of the new Exchange of Notes, even in confidence. ‘In the current case,’ Goldsmith wrote to Raab on 10 October, ‘it would be particularly concerning if it appeared that there was an attempt to conceal from Parliament an agreement which potentially impacted upon the interpretation of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations …’. Exactly.

The Exchange of Notes of 20 July 2020 was no doubt shaped by the British foreign secretary’s desperation to get the Dunn family and media off his back by showing how much he could wring out of the Americans, as well as by demonstrating his ability to prevent a similar travesty occurring in the future, even if he could not get ‘justice for Harry’. It was probably eased, too, by the Trump administration’s notorious indifference to the morale of its own diplomatic service and intelligence community. But in fashioning this agreement both governments were typically careless of wider consequences. Diplomatic and A&T officers in embassy branch offices should, by definition, enjoy exactly the same diplomatic privileges and immunities as those in the main embassy, as was clearly taken for granted in the discussions of the draft of Article 12 by the ILC and the Vienna Conference itself. To be sure, reducing immunities by means of ‘advance waiver’ rather than by definitive legal erasure leaves the entitlement of staff and their families formally in place, but in practice this is a distinction without a difference; having them in theory but not in practice is a legal nicety lost on the public, as also – no doubt – on diplomats and A&T staff as well.

Is the revised Exchange of Notes between the UK and the USA of 20 July 2020 a threat to the institution of diplomacy? It might be that the new agreement will not encourage the unsympathetic treatment of diplomatic officers as well as A&T staff at other embassy annexes because it will probably be seen as a special case: an agreement between close allies that had evolved from an existing outpost. Besides, such annexes are rare and generally not regarded as a good thing, for they could be used to protect criminal activities and, whether legitimate or not, are possibly more difficult for the receiving state to protect. The ILC thought they should be discouraged, which was why Article 12 was presented negatively (‘The sending State may not, without the prior express consent of the receiving State, establish offices forming part of the mission in localities other than those in which the mission itself is established.’). It might, therefore, be an advantage of the revised Exchange of Notes if it discourages the use by embassies of offices such as these.

On the other hand, it might well be asked: If, in practice, diplomatic officers and A&T staff are both to be denied full VCDR immunities and inviolability in a branch office such as London Annex Croughton, why should they continue to enjoy them at the main part of an embassy? That certainly is worrying. The present juncture of world affairs is certainly not a time to be playing fast and loose with diplomatic law.